[nextpage title=”1″ ]

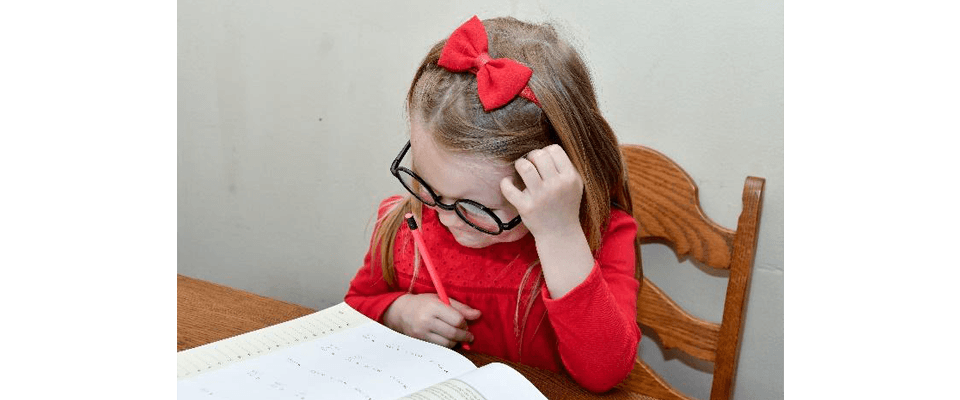

Comparatively little was known about learning disabilities when I began school in the 1960s. What educators were agreeing on then was that, if a teacher understood their subject well, all their students should be able to learn that subject. If you weren’t doing well, nobody blamed the school or the teacher. They blamed you. The only “medicine” offered to help my problem came in the form of a pinewood paddle administered via the posterior. I tried a bunch of that nasty medicine, but it didn’t cure my disability.

I did want to improve both my reading and math skills. I wasn’t fighting them or claiming the topics were too boring or irrelevant, though much of a public school education then truly was very boring for me, and much of what they assured me I needed to know became useless trivia, the kind of information you’d never need to recall beyond a test date. You see that teaching to the test is not a new invention.

For a long time, I didn’t know how to describe to teachers or counselors what I was experiencing, except frustration and anger. The result was that both reading and math were going terribly for me. I found reading difficult. Recalling the sounds of the letters and working out new and longer words didn’t seem difficult, but when my eyes moved to begin a new line of text, they would lose their place. I’d often find my eyes on the line I just read or skip past a line. It still happens now.

My problem in math was different. Numerals don’t function at all like letters for me. Remembering how to spell words correctly was easy for me, but recalling even a short string of numbers was very hard. For some reason, my short-term memory had difficulty holding any digit sequences correctly. Even when I could recall the numerals, their order might be confused. Numeric dyslexia? If that’s an actual thing, I didn’t find it searching by that name.

I was never made aware of any tutoring that was done by the school. Private tutors were an expense my parents could not yet afford. If you were clearly having difficulty, the schools typically offered only two options. The first option offered was to just make the student repeat the grade. My folks correctly guessed that it would humiliate me to be flunked into my younger brother’s grade.

The other humiliating option was special education and that was populated by kids with varying degrees of developmental delays. I didn’t want to be with the kids who had cerebral palsy or deafness or partial to complete blindness. Not that I disliked them, I just wanted to be with my “normal” friends.[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”2″ ]

I was supposed to be grateful I guess for the beatings and humiliation since it proved that they cared about my progress. You won’t be shocked to hear that it only fueled my frustration more. Next came the cancellation of my recess time so I could continue to study. They still seemed somehow shocked that that their abuse program was failing. They had already decided that failure was my job.

Discipline was judged to be my primary failure. Report cards would typically read, “Jeff is bright and highly creative but struggles with academic subjects. He needs to apply himself more in studies and complete all class and homework assignments in a timely fashion.” When a mother watches her kid begin homework after supper and work until bedtime without finishing, she knows application is not what her child is missing.

Math didn’t become a problem until I was instructed to memorize the “times table” that showed all the multiples of 1 through 12. Most multiples I could recall, except the multiples of seven and eight never took. Because the multiples of five were easy, and the same with the multiples of two and three, I would calculate these and add them. For example, I understood that seven multiplied by seven was the same as seven times five plus seven times two.

While in high school in the 1970s, I recall many occasions when four to six pages of algebraic proofs arriving at the correct answer would be marked wrong! This was because I failed to follow some specific step. To me this seemed equivalent to telling my math teacher that they weren’t MY teacher because they took a different road to school than I did. Did they want me to learn to blindly follow or solve actual problems? “Math isn’t for creativity, Jeff. Save that for your art teacher,” they’d say.

Written instructions are not held so sacred with me. Why? Imagine being left handed for a moment if you aren’t. If the directions assume you’ll be doing everything right handed then they work great but for a lefty just wouldn’t work for certain operations like hand lettering, for example. You can’t push a brush or artist pen and have it behave in the same way it would while pulling it.

So, what do you do? You figure out a different way to get the same result as the instructions are supposed to produce. If I reverse both the direction and order of every single brush stroke, the result is achieved. The book doesn’t tell you that, though. The right-handed teacher doesn’t know that either because they personally don’t need to. Nature made me left handed, not stubbornness.

Does that help you to understand that I’m creative as a survival skill? Their system made me need to be more creative each day to survive their tortures. That may sound like a harsh criticism, but I believe it was reasonable to feel tortured. To me, teachers were becoming horrible people who abused struggling children for money. The worse they did with you the more they felt justified in heaping on more “discipline and stricture.”

Public school’s failing benefited me in ways I couldn’t have imagined back then. By helping me less, they almost surely helped me more! If it wasn’t my schools job to figure out how I learn, whose was it? Accepting that schools would not change to accommodate my unique needs motivated me to find learning modes that worked for me.[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”3″ ]

I’m very visual. Often you can learn much more by just being truly observant than by asking a lot of questions. Drawing was training my brain to carefully observe objects, persons, and places. I got better at noticing things. The less you rely on what you read, the more you have to rely on the other places data is coming from. I began to become a more careful listener, using barbershop harmony like my father sang to train my ear to pick out specific parts and understand how the parts combined to create a single chord ringing a part no man was singing.

I loved that drawing didn’t require me to read really well or calculate with an audience watching. Art class quickly became my favorite subject because instead of feeling embarrassed when asked to read aloud or solve math problems at a blackboard, I displayed skill and patience others didn’t have. Many or most of my classmates who were great with math couldn’t draw much at all.

Fear of public humiliation became public school’s most effective tool. It worked the same for the year of private schooling I got in high school. Math teachers seemed to delight in waving about graded assignments bearing an enormous F in bold red marker. If the embarrassment I suffered had only positive results, I would advocate its continued use, but it had consequences on self-esteem that often lead to a range of problems later in life. When I found ways to publicly generate praise through arts, they became very important to me, so even low self-esteem can find an upside sometimes.

I finished high school with a low average grade and a part-time job. Before that day arrived, I was constantly threatened with being flunked. I had made my teachers aware that if I had failed even one subject in my senior year, I would be ineligible to graduate due to many credits lost in school transfers. My attitude had become that if they chose to flunk me as a punishment, I would make the next year as stressful for them as they had made this one for me.

I chose to enroll at a local junior college to study fine art, but I sure was sick of both school and learning. I moved into an apartment with no parents to nag me about not being late. That’s the same time I began showing up late to classes on the days I bothered to go at all. My grades convinced my parents that I should pay for all further enrollments.

I enrolled for a second semester with the primary goal of convincing my parents they were wrong about me. They weren’t. I did the second semester as poorly as I had the first or worse. I recall the exact instant that the realization that I was now wasting everyone’s time and my own money. Probably all my former college students recall what came to be known as my soup can speech. I’ll spare you the story here, but ask me because I love to tell it to college teachers and students.

[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”4″ ]

My favorite instructor at that college shook me harder. We gathered all work turned in that semester and spread it out in front of us. He knew I cared about art and painting, which was the subject of his critique.

He asked what grade I had earned on projects not turned in, and I agreed that I had earned my F as surely as I had earned my A’s. Then he pointed out I had not turned in enough projects to earn a passing score, let alone the A grade he typically gave me on all completed work. It was already too late to drop the class.

“Why didn’t you turn in all your assignments this semester?” he asked. I explained that I had to work, and since I couldn’t earn very much per hour that I needed to work more hours to catch up my bills. “If you can do either one well but not both, you need to quit your job,” he said. “I can’t quit my job. I need the money!” was my response. “Then you need to quit school.”

“You can’t tell me to drop out!” I said. Yet he already had. It made me sad he was right, even though by then I was working as a commercial artist. The job didn’t pay well and often cancelled needed hours during times I was available.

Later, while working as a projectionist, I found time to read a lot more and found types of literature I enjoyed. Within a year I had improved my reading skill by several grade levels. I learned that by reading for several hours a day for at least three consecutive days, I can overcome my eye tracking problem. When I enlisted in the military, my tested reading level nearly accurately reflected my 14 years of formal education. After applying my practice, I was easily able to read over 700 pages per day and tested at the postgraduate level for reading while in training at an NCO Leadership School around age 25 by then.

I had a very successful military career where my aptitude for learning art was exploited. In return, I exploited the government to fund my training and career development. I was promoted ahead of contemporaries and served a second term of active duty before deciding to separate.

This learning-disabled kid left the military with letters of appreciation and recommendation endorsed all the way to up to the rank of General. Yes, that’s the one with four stars who commands more people than the top three civilian airlines combined.

After a few years of underemployment, I decided to return to college so I could complete a degree program. I had an advantage in experience, but my peers typically had graduate degrees by then. I wasn’t interested in other careers, except to the extent that they’re media based. Between fine arts, commercial art experience, and cinematic film, I was already using several different resumes.

When the local state operated technical college began offering associate degrees in multimedia, I saw a chance to package all my media skills and interests under a single umbrella. I had the nerve to interview the department chair for this program before deciding to enroll. Already in my mid-thirties, parenting school aged children and a new dependent had changed my point of view a lot.

[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”5″ ]

I’m proud to tell people now that I maintained a 4.0 GPA for the first four of five semesters. Because of work commitments and transportation problems, I allowed myself to settle for a few B’s in my final semester. Now the guy my smart grade school teachers said probably wouldn’t finish high school had a college degree!

Not long after graduating I found work as a prepress system administrator where I learned all I could about print media. It was during this time I decided with my two younger brothers to start producing a television show. I worked as the show’s art director, became the lead trainer for video production staff, lead camera operator, floor manager, and eventually, the video director. I managed a set director and a webmaster too.

The television show was an immediate success at the creative level. By the end of the second season of production, we had a satellite uplink and were available nationwide. By the end of the third season, we were broadcast on over 100 PBS stations in the US and over 100 foreign countries because the show was now available via Armed Forces Radio and Television Satellite (AFRTS). We achieved that using all volunteer staff interns. I left the crew at the end of our fifth season when a fourth child arrived.

Someone asked me around then, my dad I think, why not teach? I remember that sounding absurd. “Teachers made me miserable. Why would I want to become one?” I recall asking. “There were few teachers I ever had that were any good at teaching people like me, who learn the way I do.” “Yes, but maybe you could become that teacher for someone a lot like you.” That sentence echoed in my head.

Because I had conducted a lot of vocational training since my days in the military and had a lot of very relevant and recent experience, I knew that the college I had graduated from was likely to show interest in my instructional experience since they had already hired my youngest brother on in a faculty role teaching video production.

They were interested and hired me to teach digital media design. For the next eight years, I worked very hard training many creatives. Become that teacher for the ones like you became my mission. While there, I created a drawing course for animators that quickly became the most popular course within my department, if not my entire building. It worked incredibly well because even more than I taught students to draw, I taught them a system of observation steps that allowed them to see what they weren’t noticing yet.

As an instructor, I was awarded for excellence by the state college system and nationally through an organization that honors faculty of junior colleges and technical trade schools like mine. “How do you doom predictors like me now?” I thought. What does it matter? Any of them still alive weren’t likely to remember me. But I know who will. All the students for whom I did become THAT teacher.

As a faculty advisor, I have been in the same awkward position I placed my favorite instructor in all those years earlier. Pointing out hard truths to those coasting along and phoning it in. I should add that I’ve advised more than one college student not to exploit the remediations available to them if they could still pass without them since most employers do not make accommodations of the sort the college would when employing entry level workers in creative media trades.[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”6″ ]

Too many students were struggling with remediation courses for all the same reasons they had before attempting college. The college I worked for employed many academic instructors teaching high school level learning as remediation. Students are only allowed to enroll in core curriculum courses while in remediation, so very many gave up after a year of not getting to study anything they were interested in learning at that college.

I had no way to stop the area high schools from graduating functionally illiterate students. I was shocked at the high percentage of students diagnosed with one or more learning disabilities, emotional disorders, and the myriad of other challenges. Some would require two to four semesters of remediation because of how far behind they were.

My million dollar question never occurred to me until I had been doing a faculty job for years. It stemmed from this realization. Any math teacher bright enough to offer math as a solution to art problems would have had my immediate interest, full attention, and complete cooperation.

If students can learn the academic subjects in the context of an occupation they desire along with a full appreciation for how those skills will apply, then why are no schools teaching academics this way? Teachers, you have all heard piles of lame excuses from students. You spot them when they come from schools too then.

The missing element is not rigor. It’s relevance. Get on the relevance bandwagon and watch American education blossom and American students approach learning with true zeal and excel.

Apply the Barsch Learning Style Inventory to all students before they enter high school, and teach each student the way they naturally learn. It’s more to keep track of I know, but you can group students according to needs and where that is less practical, employ CBT to track learning performance and tailor content according to student requirement.

I can refer to you to colleagues with all the coding skill required to create electronic courses which accomplish those ends if you don’t know any but many of you already do too. The U.S. Department of Education isn’t going to do it for you.

You’ll have to do the heavy lifting here, but I predict the result will make this country’s students the highest scoring in the world. Your reward will be a class filled with eager learners who are motivated to understand your subject evidenced by unassigned research based on pure fascination. Reflect for just a moment on how nice that will feel. If a teacher had done these things for me, I’d never forget them. I’d love them and work harder than ever to make them happy for rescuing me from the tedious boredom and emotional angst.

Let’s not assume learning ends with schooling because we know otherwise. In switching to an aptitude- and interest-based curricula, there are a lot of things that you won’t be doing so much of anymore like passive learning such as lectures. Students are instead paired into dyads or small teams. The team is presented a scenario, and a toolset they have been familiarized with and a deadline in which to present a working solution. How much more employable and creative are such students likely to become?

Please let me know if you agree that educators can fix most of the biggest problems schools are now faced with by simply recognizing and remediating our own learning disability.[/nextpage]

Leave A Comment